Crime prevention and other awareness initiatives for youth — whether to stop bullying, violence, drug use or impaired driving — are often delivered by police officers in a school setting. But how effective is this approach? We asked four RCMP officers about the benefits and limitations of being physically present in schools and what impact this has on young peoples' actions.

The panellists

S/Cst. Robert Cleveland, Aboriginal community constable, Police Community Relations, Thompson, Manitoba

Cst. Meighan de Pass, school liaison officer, Sidney North Saanich detachment, British Columbia

Cst. Brad Kelly, general duty investigator, Carmacks detachment, Yukon

Cst. Stephen Duggan, general duty policing, Queens District, Prince Edward Island

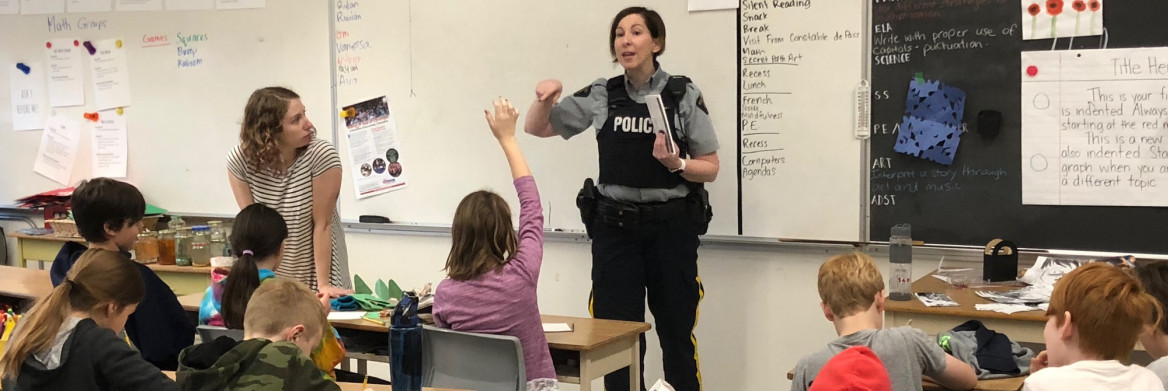

Cst. Meighan de Pass

The Sidney North Saanich detachment is an excellent example of the positive results available to a police force that invests in its youth. In response to a dramatic increase in violence involving drugs and alcohol that culminated in a murder in 1994, the detachment developed a progressive crime prevention approach in its local elementary and secondary schools.

This approach involves building a positive police presence in the schools, such as conducting safety instructions, drug abuse resistance education (DARE), bike rodeos, basic traffic enforcement, event participation and rapport-building through a multitude of avenues including officer-led sports activities.

We work hand in hand with the school administration, which leads to quick responses to in-school incidents, such as bullying and exploitation. The evolving stories from youth about bystander interventions and reporting clearly tell crime prevention officers that our education is resulting in behaviour changes.

Operationally this crime prevention through relationship-building and education results in an increase of positive exchanges between youth and general duty officers on a variety of files. Also, the better the relationship between a community and its police, the better the flow of information, which can directly benefit investigations.

An important part of developing effective crime prevention strategies is knowing your client base, and having current information is an integral part of that process. This can also manifest in decreased calls for service, a reduction in the severity of violence on youth-related calls and an increase in positive relationship-building opportunities.

When youth interact with police officers outside of liaison-based initiatives, they frequently ask about their school liaison officers. If they're in trouble, they often reference having disappointed their liaison officer, indicating the strong connection and bond that can develop between the two.

This is especially important if we consider how many youth don't have the benefit of having someone to teach and model safe, appropriate behaviours for them. They can't be positive, law-abiding students if no one is showing them what that looks like.

Children and teens often lack a safe place — or a voice to ask for one. Becoming that voice or safe person to ask can be pivotal in preventing further risky behaviours or victimization.

Some of the most important indicators of success within this field are anecdotal. Recently our former school liaison officer received a text from a former student. She was letting him know that due to his support, she had just successfully provided testimony in court.

Our continued presence in our schools directly combats the often negative social media pop culture interpretation of police officers. Building relationships with young people has immediate benefits for society and it will reap further benefits as these youth become our clients of the future.

S/Cst. Robert Cleveland

I have a very unique position as an Aboriginal Community Constable working and living in my own community. I have worked as a police community relations officer with the Thompson RCMP detachment for the last six and a half years.

Being Métis has opened many doors. I've been a school liaison in several of our local schools. I have taught the DARE program as well as the Aboriginal Shield Program to a variety of classes both in urban and rural areas. I've also been invited to speak to children about drugs, stranger danger, the buddy system, recruiting and sexting. School visits occur almost daily.

Whether it be to meet the teachers or to participate in Remembrance Day services, the National Aboriginal Veterans Day, a Christmas feast, Citizenship Day or school science fairs, I have the opportunity to discuss issues with the students. I've also been included in many school functions and sit on several committees such as the Adolescent Health Education Committee.

Finally, I also make myself available to the schools should they have concerns or issues that they need addressed: bullying, internet concerns and some behaviour issues.

I feel that by being present in the schools fosters positive relations with the staff and students. The students are shown that police officers are human beings and that we care about them. Being in the moment and engaging with youth in the schools helps to build healthy relationships.

Students are not afraid to approach police officers and this reduces the barriers not only in the school but outside as well. As a SAFE (school action for emergencies) co-ordinator in Thompson, I practise lockdown drills in the schools. This sends a very powerful message to the students and staff that police officers are there to keep everyone safe. It calms students and reassures them that the police are there to help protect them.

I have found that many students are curious about the job of a police officer and by being physically present, this allows students to engage with the officer and ask questions, share ideas and thoughts, and see another perspective.

Engaging with Indigenous students especially helps to dispels myths, rumors and non-truths about police officers, and being in the school allows this to happen. Yes, some people have negative perceptions about police, but there are many others who have had positive interactions.

There are many great police role models within this organization and members who care about schools and the communities in which they live. I have witnessed this through positive initiatives such as the National Youth Engagement Week, the National Youth Leadership Program and the Aboriginal Pre Cadet Training Program, to name a few. These programs only strengthen our relationships within the schools.

Having police officers in schools builds healthy relationships with the students and this makes a difference.

Cst. Brad Kelly

Prior to my current posting, I worked in Watson Lake, Yukon, for three years. During that time, I had many opportunities to engage in community policing with young people.

On a couple of occasions, I accompanied a First Nation youth to the RCMP Training Academy in Regina, Sask., for Youth Leadership Workshops. These workshops were tailored toward First Nations youth from different communities across Canada. They focused on empowering young people to create and implement action plans in their communities to help address issues related to victimization. The workshops also served to develop leadership skills in youth and help build positive relationships with police.

The youth who I guided identified bullying to be a pervasive problem within Watson Lake. She and I created a plan to implement the Walk Away, Ignore, Talk it out and Seek Help (WITS) Program, which aims to prevent bullying and peer victimization.

We attended the kindergarten and grades one, two and three classrooms at the local elementary school, and read age-appropriate and culturally relevant stories about bullying to the students. Following the readings, we led discussions about the material. We might ask students why the main character felt left out or what the other characters could do to include him or her.

Being in the school allows police officers like me to work from a strengths-based perspective in that we aren't there to catch young people doing things wrong; rather, we're there to promote youth empowerment.

It creates opportunities to connect with young people in a positive way and to become a meaningful role model. By being approachable, police officers can show that they are there to help rather than solely to hold students accountable for wrongdoings. Police presence in schools enforces the idea of community-based policing and helping families and community members enjoy life.

In the school, I've not only built relationships with young people but also with school personnel. I've collaborated with teachers working toward the same goal of reducing peer victimization. In many ways, the RCMP and the education system are very much on the same page when it comes to healthy promotion of individual strengths and opportunities for youth.

One limitation of any sort of crime prevention initiative is that there's no one-size-fits-all approach. When delivering the WITS Program, I was well aware that children come from different backgrounds and home lives and it may be difficult for every one of them to simply walk away, which is the first step in WITS. I was also aware that they may need to internalize this information through repetition.

Finally, I was able to learn from the youth by interacting with them in the school. Young people have their finger on the pulse of what's going on and it can help police officers remain current and responsive to today's issues as experienced by youth.

Cst. Stephen Duggan

The key to speaking on any topic from a police standpoint is to make the subject real for the student and show them that I'm not just another adult telling them not to do this or that. I'm lucky that my "You control the choice you make

" campaign involves something all teenagers want to do: drive a car.

My presentation is a direct result of receiving a letter several months after I had arrested a young person for driving impaired. This driver wrote about what that one bad choice had cost her — losing her job and education, feeling humiliated among family and friends, and the ongoing monetary cost of getting her licence back. But even after all that had happened, this young driver thanked me for stopping her because it changed her life.

As a police officer, I knew I had found the real story around which to design a presentation.

I learned early in my career that showing up unprepared is worse than not showing up. For the school to give valuable class time, especially an entire school, there's an expectation that the message you deliver make a long-lasting impression on the students.

I always open with, "I'm not here to tell you what you can and can't do. I'm just here to explain the consequences of the choice you make." Over the next 40 minutes, I discuss the various police interactions they can have based on the driving choices they make. I make it interactive by having students provide a breath sample on a roadside screening device, go through a mock Standardized Field Sobriety Test (SFST) exam followed by telling them they are under arrest.

I conclude my presentation by telling the students about that young driver who wrote me the letter. I then stop and bring that young driver out. For about 15 minutes, the students get to see and hear a peer telling them the consequence of making a bad driving choice. I tell the students that this driver made the wrong choice, but instead of letting it define the rest of her life, she made a better one — and standing in front of them to tell her story is part of that.

This presentation allows me to incorporate and remove subject matter when necessary. With the changes to marijuana laws coming in 2018, I have already started to incorporate more impaired-by-drug information into the presentation.

I know my presentation works. In Prince Edward Island, I have policed in two districts and have spoken in the district high schools annually and driver education courses monthly. I've had students and young drivers follow me into parking lots, just to tell me that they've made the right choice.

I'm positive that without the support of schools giving their valuable class time, students wouldn't have the opportunity to meet a police officer, interact with them and be provided with valuable information. It's much easier to make these students accountable for their life choices when they've all heard the message together at the same time.